|

George and Sophia's eldest son John, was Lang Hancock's grandfather and their second daughter

Emma, married John Withnell and was to become known as the

'Mother of the North'.

When John Hancock and his sister Emma (now Withnell), their 15 year old sister Fanny Hancock, along with John Withnell, his brother Robert and three

servants went north aboard the small ship Sea Ripple, a long association between the Hancocks and the Pilbara region had begun. They established

the first port in the North West at Cossack and travelled inland to build their homestead at what was to become first town in the north west - Roebourne.

After the Withnells had established Mount Welcome Station, John Hancock returned to Perth, married Mary Strange, had two daughters and applied for land

near Roebourne which was to become Woodbrook Station. It was here in May 1882 that George Hancock (Lang Hancock's father) was born. The family

moved south to Northam but soon afterward Mary died aged only 37.

John went north once more seeking gold at the Halls Creek fields but having no luck he bought a share of the Ashburton Downs station near Onslow. John

Hancock died in 1902 leaving his three surviving sons with 6000 pounds each (their sister who had to look after the family after their mother's untimely death)

apparently got no interest in the Station.

Ashburton Downs was now to be managed by each Hancock brother in turn. Richard and John (Jr.) showed neither the ability or the interest to run the station

properly and when George had his turn at managing the Station, it was in serious disrepair. He met and married Lillian Mabel Prior in Onslow and they moved

out to Ashburton. It quickly became evident that under the management of the elder brothers, the station had been badly run down.

During the six years his brothers were managing Ashburton, George was offered the job of Manager at Mulga Downs. Seeing the writing on the wall for Ashburton

he took the job and went on to buy Mulga Downs from its owner Frank Wittenoom.

On June 10 1909 Langley Frederick George Hancock was born. Lang went on to take over Mulga Downs station and at the end of the season (16 November 1952) when

he and his second wife, Hope (formerly Nicholas of Cobb and Co), were flying out on the way back to Perth in their light plane, they had to detour as huge clouds

rolled in. (2)

Forced to fly lower than usual because of the clouds, the small plane had to be flown down through a gorge. Lang noticed what he thought could be iron ore deposits

and kept it in mind until he had the chance to return for a better look. He assumed that the ore must be low grade as no-one had reported its existence even though

surveys had been done in the region. When he flew over the area again he saw that it continued for so many miles that it must have some commercial value. He took

samples over 50 miles and sent them to Perth for analysis. They turned out to be 2% higher than the then standard blast furnace feed of the United States of America.

At the time there was an embargo on the export of iron ore as the Federal Government's position was that Australia had insufficient reserves of iron ore. Lang's find

was technically worthless. He had been involved in prospecting and small mining ventures since 1938, and Lang knew that at some future date the iron ore would be

worth millions, but only if able to be pegged, developed and exported. Lang Hancock lobbied strongly for the law to change.

The embargo was officially put in place because it was claimed that Australia's iron ore reserves were a mere 358 million tons. Before the Second World War, when

Japan was emerging as a threat in the region, the government decided not to allow iron ore to be exported as they feared getting it back in the form of bullets and

bombs. This did in fact eventuate as the Menzies Government, in an attempt to mollify the Japanese, began selling them scrap iron, much of which was to be turned

into war material. Robert Menzies was given the nickname 'pig iron Bob' for that decision.

By the 1950s Japan was a 'friendly' nation and as its need for iron grew, it was seen as a potential market for the ore that was doing nothing in the Pilbara. The problem

was that there was no infrastructure and the WA State Government had even placed a ban on the pegging of iron ore! Apart from that there was no infrastructure in the

north west. Towns, power plants, railways, ports and mines all needed to be constructed and this would take millions of dollars.

Lang spent some time flying around the Pilbara mapping the iron ore deposits, and many years later, was helped in this endeavour by Ken McCamey. How was it that

between them they managed to find around 500 large ore deposits when state government and BHP aerial exploration didn't find any after flying over the same country?

The answer is as simple as it is embarrassing for technology. High tech ore body detection was done with instruments that were supposed to spike in the presence of

high concentrations of iron ore. The instruments showed no spikes so it was believed there was no iron. The problem seems to have been that there were no spikes

because the areas explored had such high concentrations of ore that the instruments failed to act as they were supposed to. Lang and Ken had simply used their

eyes to find what they were looking for.

Lang is quoted as saying the following about his discovery and the subsequent problems getting people to recognise what he had found:

'Well people knowing this throughout the world, people interested in iron ore, knew that there was no iron ore in Australia and here was I, a boy from the bush,

no experience, no education, no letters after his name or anything, trying to tell them that I'd found by far the world's largest iron ore deposits, a whole field actually

and you know, 30 or 40 firms throughout the world said "run away, it's a lot of rubbish".

Unbeknown to me, they rang up what was then known as the Bureau of Mineral Resources in Canberra and Doctor Argot, the head of it, said Hancock's talking through

his hat, we've done a magnetometer survey of all that area and there's nothing there. So then they came back to me and I said well look if there's something there you

pay me a royalty - if there's nothing there it doesn't cost you anything.'

Lang had the problem of getting overseas mining companies interested in starting up without revealing exactly where the huge deposits he had located were. Letter

after letter met with refusal and Lang was even frozen out of the first mining venture.

Gradually overseas investors started to take notice and the first mine at Goldsworthy was opened. It was a mere pimple compared to what would come later but it

was a start.

Finally in 1961, Rio Tinto sent out a geologist (Bruno Campana) to check on Lang's finds. Bruno was impressed with what he saw but the head office of the

Australian arm of Rio Tinto (in Melbourne) dragged its feet, causing Lang Hancock to go over their heads to the Chairman, Val Duncan, in London. This made

Lang very unpopular with the Australian staff of Rio Tinto, who even refused to give Lang the credit for his discoveries, despite having his maps in their office and

having to pay Lang's and his partner's companies royalties.

At last, in June 1963, an agreement was finalised and Lang lived to see the Pilbara boom with the development he had so badly wanted for that remote region.

Along the way Lang had made some powerful enemies. He was a practical, if somewhat blunt man, and could never suffer fools gladly. His lack of diplomacy rubbed

Premier Charles Court the wrong way and Lang made no secret of his dislike of 'bureaucratic management', committees and politicians that held up progress. Lang

appreciated men who made things happen and learned early on that if you wanted to get something done, you went straight to the top. In 1966 at the opening of the

Hamersley Iron project, Lang Hancock's name on the guest list was conspicuous by its absence. He was not even mentioned in any of the speeches that day. The

local bureaucracy had shut him out, and went on to spend many years denying him credit.

2 Years after Hope Hancock died, Lang married Rose Lacson (his housekeeper), whose past history in the Philippines is somewhat murky. Rose was 36, Lang was 76.

Lang's previously close relationship

with his daughter Gina (Georgina) became strained, and the family company he had started went rapidly down hill after his marriage to Rose. Assets in the

Pilbara (Marandoo, McCamey's Monster, etc.) and elsewhere were sold and dissipated. Thankfully Lang's trusting relationship with his daughter was regained

prior to his death and his relationship with Rose became increasingly estranged. (Not only were they separated, but Lang took out a violence restraining order

against Rose to prevent her visiting him.)

Gina rebuilt the family company and continued her father's dream of owning and operating their own mine as well as continuing to develop their beloved Pilbara.

The dream was eventually realised by Gina and in her mother's honour, the 'Hope Downs' mine opened for business.

Among other names that should be remembered as helping to get the iron ore industry started is

Stan Hilditch who also found his mountain of ore near Newman 5 years after

Lang had found his canyon. Both men had to wait a long time for their dreams to come true. In the end Stan became a multi-millionaire and Lang, thanks to his

efforts, became one of the richest man in Australia with around $50,000 a day pouring in royalties that he shared with his partner, Peter Wright .

As a strange footnote to the story of iron in the north west, Arthur Bickerton (the local member for the Pilbara from 1958-1974), Stan Hilditch and Lang Hancock

all died in 1992. An era had ended.

Lang Hancock's legacy can be seen today in the iron mining and shipping towns of the North West. Karratha, Dampier and Tom Price and the railways between, all

owe their existence in some way to the vision and efforts of one man. While he was not the first to report finds of iron ore in the Pilbara and he was not responsible

for most of the development that has occurred, he was definitely a major driving force in the establishment of a huge export dollar earning industry for Australia.

Of Australia's top 50 iron ore mines that are operating today, no less than seven are based on ore discovered by Lang Hancock.

Many people have tried to run Hancock down over the years. From criticism of his right wing views, to unfortunate comments regarding his personal life in his final

years. Lang came from a background where there was a right way to do things and a wrong way to do things and there was no grey area in between. This did not

quite fit the new liberal views held by people who had never ventured far from city comforts and who knew little of what was needed for the state's north west.

It has to be said, though, that Lang did have some very odd ideas including using controlled nuclear blasts to break up ore bodies and create harbours. The state government

even cautiously supported his idea to set off a nuclear explosion at Cape Keraudren, to create a harbour. Thankfully this did not eventuate. Other oddities include the

sterilisation of the Aboriginal people by putting chemicals in their drinking water. Lang also supported Queensland Premier, Joh Bjelke-Petersen, for Prime Minister.

Lang was in favour of 'small government' and resented government interference. His is quoited as saying : "I have always believed that the best government is the

least government... ...Although governments do not and cannot positively help business, they can be disruptive and destructive."

|

|

In her book, 'Lonely for my land', Tish Lees says of Lang;: "With Lang, what you saw was what you got. There was no pretence or posturing or beating about the

bush. He didn't suffer fools gladly and was indifferent to what people thought of him."

Tish relates a story about Lang during his jet-setting travels to other countries. His pilot accidentally dropped Lang's dilly bag on the tarmac and when he investigated

the contents he found a tin plate, can opener and two tins of camp pie. When the pilot asked Lang about it Lang replied : "With the tucker they dish up over here you

can't eat, you never know when you might need a decent feed."

With all his money and the trappings of success, Lang was still a 'bushie' at heart.

Lang Hancock may have been 'lucky', but more importantly, he was practical man and hard worker. He had lived in the Pilbara himself and understood the problems

of living in such a harsh remote place. Lang's tireless efforts would eventually make all the difference by attracting essential development to the region.

In the beginning he was stymied by Government for years and ignored by the major companies he approached, but in the end the huge iron ore industry we have

today owes it's continued good fortune in large part to Lang Hancock. Billions of tonnes of the ore he discovered have been exported, earning Australia billions

of dollars and helping to improve our standard of living.

Kaiser Steel, who worked closely with Lang Hancock and were particularly involved in bringing to fruition the Tom Price Project, were one company that recognised

Lang Hancock's achievements and wrote of him:

'More than any one man, Lang Hancock is responsible for the Hamersley Iron development... ...Without Lang Hancock there would be no Hamersley Iron.'

(Read the complete text.)

In 1999 the Hancock Range in the Pilbara was named in Lang's honour.

(1) - Needs verification.

(2) - The account of the ore discovery in 1952 and the flight down the canyon to avoid a storm, has been challenged in at least one book which states that no

weather records exist to show that the thunderstorm actually took place. The lack of weather data is not all that surprising as the Pilbara was (and still is) a

remote area with little instrumentation to record weather events away from settled areas. We have to wonder why anyone would bother to challenge Lang

Hancock\'s account of the discovery in any case and we can see no reason why he would simply make it up.

(3) - Hilda Kickett claims she is Lang's illegitimate daughter from a liaison with and Aboriginal woman but her claim has not been upheld.

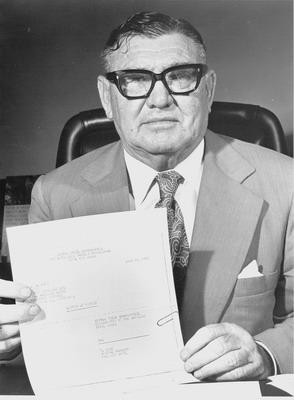

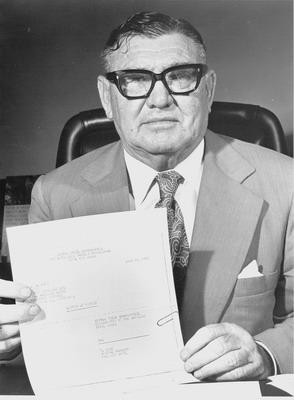

Our sincere thanks to Sharon Kennedy, Assistant Information Manager of Hancock Prospecting for helping to compile this information and for the photos of

"The Man of Iron".

|

Lang Hancock

|

|

Chronology

1909 - Born June 10th.

1935 - Lang married Susette Maley on October 16th.

1938 - Starts a partnership with Peter Wright and forms 'Hanwright'. During the 1930s Hancock was involved in mining asbestos at Wittenoom.

1943 - CSR becomes involved with the Wittenoom mine.

1943/4 - Served part time as a sergeant in the 11th North-West Battalion, Volunteer Defence Corps.

1944 - Lang and Suzette divorced.

1947 - Lang married Hope Margaret Clark (Nicholas) on August 4th.

1948 - Lang and Wright sell out of the Wittenoom mine. They begin mining at Nunyerry Gap.

1952 - The 'Discovery flight' took place in November.

1953 - Lang returns to the discovery site and takes samples of ore.

1960 - Lobbied for ore export embargoes to be lifted. They were but the state government imposed a ban on exploitation of resources not already pegged.

1961 - Pegging of the discovery site takes place.

1962 - Negotiation of agreements with Rio Tinto.

1962 - Japanese steel firms begin to take an interest in the discovery.

1963 - Extends exploration of the Pilbara for more sites.

1966 - CSR closes the Wittenoom mine and Hanwright re-purchases it with the idea of using Wittenoom as the operational centre of a vast mining industry..

1969 - Starts the Sunday Independent newspaper.

1973 - Paraburdoo site begins production.

1974 - Lang gets a jet pilot's license. Starts the newspaper The National Miner.

1979 - Lang writes the book 'Wake Up Australia'.

1983 - Hope died.

1985 - Married Rose-Maria Lacson on July 6th. At around this time Lang begins to have a falling out with Gina.

1987 - Negotiates with Romania to swap iron ore for the infrastructure needed to start a mining venture at Marandoo. Latrer Gina was to withdraw from the

deal that cost Hancock Mining a reported 40 million dollars.

1990 - Channar starts production.

1992 - Died March 27th. An 11 year battle over Lang's estate then ensued between Gina and Rose.

NB. Just three months after Lang's death, Rose Hancock married property developer William Porteous.

Links to more information:

Lang Hancock

Hancock, Langley Frederick (Lang) (1909-1992)

The Maid Who Married The Boss

|